I hear so many educators pontificate about ‘maintaining standards’. In developing countries, there is a cry of, “Don’t water-down the curriculum” from the standards of Harvard, Oxford, and other top Western universities.

This attitude usually comes from local scholars who have achieved their advanced degrees from top Western universities. When they return to their home countries, they feel, “I worked hard, and if I was able succeed, other students in my country should achieve the same standards.”

These success stories come from the creme-de-la-creme, who had been miles ahead of other students in their local classes. The majority of students in these countries, coming from poor schools with poor teachers, don’t have a hope of reaching the levels of Western universities. They often give up and drop out. Their education has been largely a waste, a sacrifice to that top echelon of elite students who may receive overseas admission.

There are games being played to pretend that a university is maintaining ‘standards’. One is to require 800-page Western textbooks that the students cannot read. (In a foreign language, no less) A more subtle method is to test memorization rather than understanding. I was amazed at the memorizing abilities instilled by many African cultures. I saw little kids at Koranic schools learning to recite the ENTIRE Koran by heart in Arabic, of which they understood not a word.

I used to teach mathematics in developing universities. A typical calculus exam question might be “State and prove the Fundamental Theorem of the Calculus.” And the students could do it — pretty impressive evidence that they were achieving Western standards — except that many of them just memorized the words from the textbook without having a clue what they meant.

How high do you set the high-jump bar?

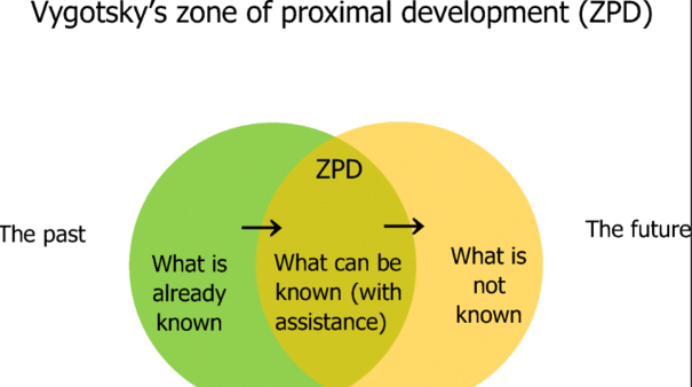

That’s where Lev Vygotsky comes in. This Russian psychologist is known for his concept of ‘Zone of Proximal Development’, or ZPD. This ‘zone’ is the gap between where a student is and what he is willing or able to achieve. I’m aware that my interpretation of the ZPD may not exactly match Vygotsky’s, but I visualize it as a high-jump apparatus. If you set the bar too high, the student will not be willing to attempt the jump, but if you set the bar too low, the student will not be interested or engaged enough to jump. Of course, each individual student will have their own ZPD, so it is the teacher’s job to find that ZPD and set the bar just high enough to engage the student to jump. Then the bar can be gradually raised as far as the student is willing to attempt it.

I actually witnessed an actual high-jump in Cambodia, where a well-meaning NGO set up many high-jump pits on rural schoolgrounds. They ordered the best — Olympic standard apparatus — so that the lowest peg was far higher than the little kids could jump. The high-jump pits were totally ignored, and the once-sand-filled landing pits became filled with mud and often cow dung. If the NGO had only set up lower bars, they might have interested the kids into attempting to use the apparatus.

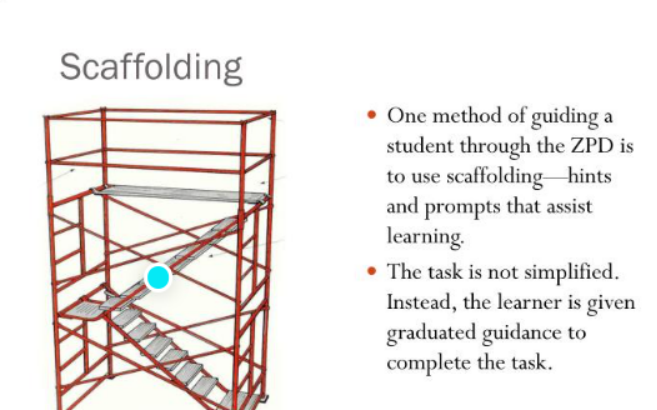

Vygotsky used the term ‘scaffolding’, because a scaffold is a series of steps that leads to the summit. The teacher sets these achievable steps for the student, who proceeds, step-by-step, to the top.

In my experience, I have written a whole bunch of easy-to-read textbooks in various university subjects. When I taught the courses using my own materials, students were engaged enough to learn, while in other courses using the 800-page textbooks, there was very little learning. Alas, my materials were not usually welcomed by the elite educators, who accused me of watering down the curriculum. They returned to pretending to use the 800-page texts.

These elitists are supported by Ministry of Education officials, who themselves were part of the elite cadre who succeeded in overseas education, and who had adopted that mentality of catering to the top 10% of students who might qualify for study abroad. So the Ministry officials thought, “If I was able to read an 800-page textbook when studying in the USA, then local students should be forced to do the same.”

In order to study abroad, a student must pass a TOEFL or IELTS or DuoLingo exam, geared to the English of analytical thesis reading and academic writing. The typical non-elite student — let’s say a Finance major — will need a different sort of English: the English of working in a bank, such as waiting on customers, reading banking regulations, etc. These students are being short-changed, since the English taught at all levels is aimed at the eventual study-overseas target, and not at the Finance major.

Thus, I feel that education in developing countries should follow the Vygotsky high-jump/scaffolding method, aiming to educate every student according to their individual ZPD, rather than catering only to the elite 5% or 10% who may qualify for study overseas.